Vizionarul Lord Norman Foster/ The visionary Lord Norman Foster

Lumea va trece de la „eu, eu, eu” la „noi, noi, noi”

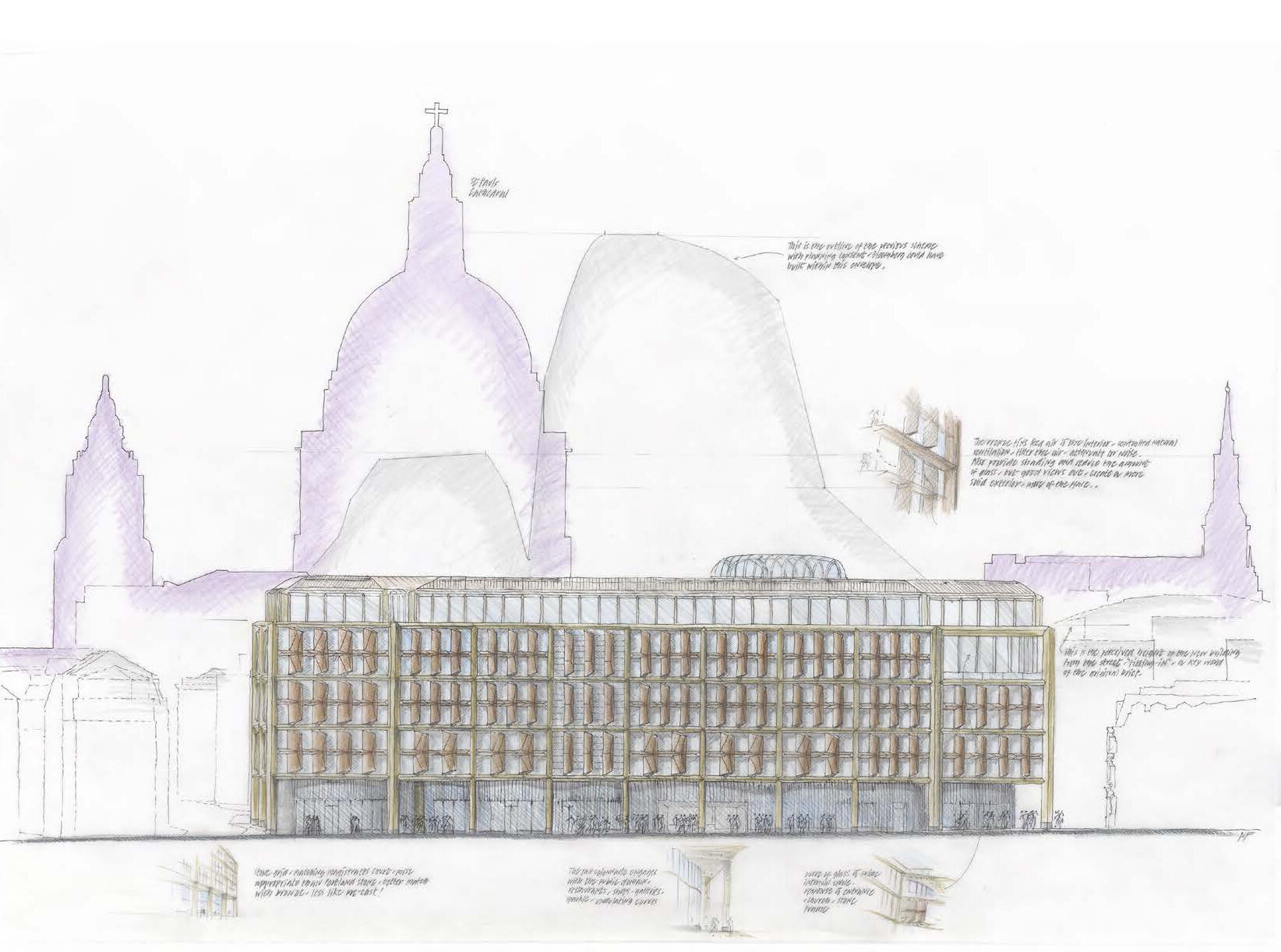

Arhitectul britanic Norman Foster, iconic pentru arhitectura high-tech, se dovedește a fi, în nebuloasa perioadă marcată de pandemia Noului Coronavirus, unul dintre vizionarii care abordează problemele globale ale omenirii și arhitectura în contextul frământărilor la nivel planetar, cu determinantele și consecințele lor în plan social, economic, tehnologic.

Norman Foster cuvântează la ONU, la Forumul Primarilor, la marile reuniuni mondiale. Părerile sale sunt preluate și dezbătute de presa din întreaga lume. Implicarea sa în problemele fundamentale ale planetei nu sunt de dată recentă, ci se referă la o activitate de mai bine de 50 de ani.

Întrebat despre importanța schimbărilor la nivelul arhitecturii, dar și al conceptelor de dezvoltare urbană, în perioada viitoare, Norman Foster a răspuns că pandemia nu va aduce schimbări neașteptate, surprinzătoare, ci va accelera tendințe deja cunoscute, dar neluate în seamă, cu seriozitate.

Arhitectura sustenabilă, practicată astăzi ca exceptie, va deveni tendința principală, așa cum orașele vor ocroti mai curând locuitorii decât autoturismele, spațiile verzi vor deveni un mediu cotidian de viață și transportul în comun terestru va fi înlocuit de monoraiurile aeriene, munca se va desfășura mai mult de acasă, dar și din locuri neconvenționale, alimentele vor proveni mai mult din fermele urbane etc.

Arhitectura și sănătatea

În raportul anual al firmei care-i poartă numele, Norman Foster a făcut o analiză a fenomenelor prin care trece lumea construcțiilor la nivel global și a evocat relația dintre viața orașelor și sănătate, de-a lungul istoriei. Bolile, molimele, epidemiile au fost, în mod paradoxal, motorul unor uriași pași spre progres: holera de la Londra, de la mijlocului secolului al XIX-lea, a grăbit introducerea rețelei moderne de canalizare și salubrizarea, tuberculoza newyorkeză a tras un semnal de alarmă față de necesitatea spațiilor verzi în oraș, pandemia de gripă spaniolă de la începutul sec. al XX-lea a declanșat programul de sanatorii, terase în aer liber, baze sportive și bazine de înot, pereții albi și recunoașterea calităților terapeutice ale luminii și aerului curat, „Marele Smog” din Londra a condus la instituirea Legii Aerului Curat și a grăbit înlocuirea încălzirii cu cărbuni prin cea pe gaze naturale. Fără a fi cauza fenomenelor, crizele medicale au fost catalizatorul, „ocaziile” care au grăbit și impus rezolvări ale problemelor „mocnite”.

Arhitectura sănătoasă

Referitor la actuala criză, Foster abordează definiția arhitecturii sănătoase și tendințele acesteia ca arhitectura viitorului.

„Încă din 1967, când am înființat firma, am elogiat calitățile clădirilor sănătoase care pot respira și interacționa cu natura, pentru a obține un mediu interior controlat și care, în plus, să consume mai puțină energie.”

The world will switch from ”me, me, me” to ”we, we, we” !

Norman Foster, the British architect who is iconic for high-tech architecture, proves to be, during the turbid period marked by the New Coronavirus pandemic, one of the visionaries dealing with/addressing global issues of mankind and architecture, in the light of worldwide convulsions bringing about social, economic and technological consequences.

Norman Foster delivers speeches at the UNO reunions, at the Forum of Mayors and other important world reunions. His opinions are taken into account and debated in the international press. His involvement in the fundamental issues of the planet is not recent, dating back to his over 50 year-long activity.

As a reply to questions related to the importance of future changes in architecture and urban development, Norman Foster asserted that the pandemic would not bring about unexpected, surprising modifications, but it would accelerate trends that were already underway, but were not taken seriously.

Sustainable architecture, which is exceptionally practiced today, will become the main trend and cities will protect their inhabitants to the detriment of vehicles, green areas will become an everyday living environment and public terrestrial transport will be replaced by aerial monorails, work will take place mainly at home, but also in other nonconventional places, food will be supplied mostly by urban farms etc.

Architecture and health

In the annual report of his architectural company, Norman Foster examined the trends in the global construction field and underlined the link between the life of cities and health issues along history. Diseases, plagues and epidemics were, paradoxically, the driving force of huge steps towards progress. The 1850s cholera outbreak in London led to its modern system of sanitation and sewerage, the New York tuberculosis pointed to the need of green spaces in the city, the Spanish Flu pandemic in the early 20th century brought about the program of building sanitariums, terraces, sports centers, swimming pools, white walls, as well as the recognition of the restorative qualities of light and fresh air. The 1952 'Great Smog' of London led to the creation of the Clean Air Act and was a catalyst for the move away from coal fires to gas. Without being the cause of the phenomena, medical crises were the catalyst, ”the opportunities” that hastened and imposed the settlement of ”latent” issues.

Healthy architecture

With reference to the present crisis, Foster addresses the principles of healthy architecture and its trend to become the architecture of the future.

”Since I founded my practice in 1967, I have been extolling the virtues of healthy buildings that can breathe and work with nature to produce controlled indoor environments that, in addition, consume less energy.”

The principles of healthy architecture imply:

Since the 1970s of last century, Norman Foster has been a pioneer of new values and a searcher of solutions to global issues of mankind. The oil crisis and the concern for the waste of energy, the significant interchange with nature brought him close to Buckminster Fuller, another visionary of the 20th century. Between 1971 and 1983, he collaborated with him, being driven by his mindset of ”an impatience and an irritation with the ordinary way of doing things”.

Norman Foster designed four projects, in collaboration with Bucky, which were catalysts in the development of an environmentally sensitive approach to design.

Their first joint project, the Samuel Beckett Theatre, was an auditorium buried beneath the quadrangle of St Peter's College, Oxford, 'like a submerged submarine'. The project failed to attract sufficient funding, but it involved research into underground structures which was to inform later projects.

The Climatroffice project, a transparent tensegrity structure with its own internal microclimate, enclosed landscaped office floors. Although purely a research project, it inspired the subsequent urban scheme for the Hammersmith Centre.

The design Study for the 1978 International Energy Expo in Knoxville, Tennessee, was a lozenge-shaped tensegrity structure with a double skin, capable of containing the entire exhibition in a climate-controlled enclosure. It included a wide range of solar heating, cooling and electricity-generating devices to maintain optimum comfort conditions.

The Autonomous House was the design of two prototype houses, one of them in Los Angeles for the Fullers and an identical one in Wiltshire, England, for the Fosters. The dwellings were to be double skin geodesic domes, both the inner and the outer one (measuring 15 metres in diameter), being free to rotate independently. The two skins would be half glazed and half solid/opaque, so that, at night, the dome could be shut off completely, while during the day it could follow the path of the sun. Warm or cold air would circulate between the two skins, depending on the season. As in the Climatroffice project, the cooling properties of certain plants would be harnessed to create an internal microclimate. Work on the project ceased with Fuller's death in the summer of 1983, but the environmental ideas it embodied resonate in the design of the Reichstag's cupola with its moveable sunshade.

· Sustainable office buildings, with energy performances

The first building designed in the spirit of the beneficial dialogue with nature was the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, also dating back to the early 1970s. Half century later, the most recent projects of the practice are the headquarters buildings for Bloomberg News Agency in London and for Apple Company in California. Tall buildings were achieved in-between, starting with Commerzbank in the 1990s, which demonstrated the feasibility of a naturally ventilated skyscraper.

At the Commerzbank Headquarters, the central atrium functions as a ventilation ‘chimney’ drawing fresh air through its windows that can be open. With its four-storey high sky gardens, it is considered to be the first ecological high-rise. (Annex Photo 13)

”These breakthroughs in the pursuit of a healthier and lower carbon workplace have only been made possible through a combination of research, passionate advocacy on our part and enlightened patronage by corporate leaders who seriously care for the welfare of their work place. This trend, which is currently a 'fringe' movement, will become mainstream in terms of new buildings” – the architect says.

For decades now, there are over fifty rating systems that judge the performance of buildings in terms of their sustainability. The BREEAM and the LEED systems are preeminent. The Bloomberg headquarters project has achieved the highest BREEAM rating so far recorded for an office building. A new WELL rating has recently emerged, as a reflection of the trend to raise concern, not just about the building, but the wellbeing of its customers. The headquarters of the Hearst Corporation was the first building in New York to be certified LEED Platinum and has achieved the first-ever WELL rating in the metropolis.

The Bloomberg building has soon become iconic for the City of London, by its architecture and location. It is an example of sustainable development, with the highest energetic score ever achieved by any major office development.

Occupying 3.2 ha, the site comprises two buildings united by bridges that span over a pedestrian arcade that reinstates Watling Street, an ancient Roman road that ran through the site. Bloomberg Arcade is now a key route for the City, animated by restaurants and cafes at ground level, set back behind an undulating façade in glass. Three public plazas, located at each end of the arcade and in front of the building’s entrance, provide new civic spaces in the heart of the Square Mile.

The building also integrates the archeological remains of the Roman Temple discovered on the site, as a cultural centre.

A distinctive hypotrochoid stepped ramp, characterized by its smooth continuous three-dimensional loop, flows through the full height of the building, adding to the drama of the interior space. Clad in bronze, the ramp is designed and proportioned as a place ofsocialization.

Apple Park creates an ideal workplace for creativity and innovation. The campus is Californian in spirit, being connected to nature. Its landscape and buildings form a seamless whole: the Ring Building, Steve Jobs Theater, the Fitness & Wellness Center, the Visitors’ Center and the South Parking are all marked by socialization, sporting life and creative work. The flexible and minimalist architecture is integrated in the park, amid tall trees; it draws its energy from the sun and brings the invigorating views and fresh air from the park through its glass facades. The building has been designed with a deep care towards the environment, the company and its staff. The campus is powered by 100% renewable energy and is on track to be the largest LEED Platinum-certified building in North America. The green spaces have been increased from 20 to 80% out of the 71-hectare field (with 9,000 trees, as well as meadows, sports fields, terraces and a pond), while walking and jogging trails are six kilometer-long.

The Ring Building conceals immense expertise and innovation, comprising a few core elements: communal ‘pod’ spaces for collaboration, private office spaces for concentrated work and broad, glazed perimeter walkways – featuring the largest sheets of curved glass ever constructed – that allow uninterrupted connection to the landscape. The Ring’s floors are made of the most advanced precast concrete structures in the world. These multiuse elements, known as ‘void slabs’, form the structure and the exposed ceiling, incorporate radiant heating and cooling and provide air return. At the eight cardinal axis points, full-height atria create light-filled entrance commons: social spaces that connect the park to the garden space within. The Restaurant occupies the Ring’s entire north-east axis. Its quadruple-height dining hall and outdoor terraces encourage interaction. Most impressively, the Restaurant’s north-eastern facade can slide quietly away. Huge doors of glass, 15 metres high and 55 metres wide, the biggest of their kind ever constructed, roll effortlessly on tracks beneath the floor. They enhance the sense of landscape sweeping through the building.

Several other buildings form an integral part of the experience at Apple Park: The Fitness & Wellness Center is a pavilion retreat in the landscape, composed of a pair of single-storied, lightweight buildings; an expansive glazing opens the exercise rooms onto the parkland.

o The physical health of employees and the work amid nature

Foster+Partners has involved in the promotion of social peace since the early 1970, when the Fred Olsen shipping line managed to avoid the dock workers riot in the London Docklands thanks to the design practice and its project promoting a new lifestyle, which also included sport facilities for exercising at the workplace.

In 1973, the project for the headquarters of the company in Norway proposed a series of buildings located in a pine wood near Oslo:

This proposal provided a series of pavilions informally arranged in a pine forest near Oslo. Reached by pedestrian routes laid out along existing ski trails, the pavilions are lightweight single storey enclosures, being designed with the care to not disrupt the delicate forest ecology and to conserve energy (at the time of the 1973 fuel crisis).

The buildings were intended to respond, chameleon-like, to changes in the environmental conditions. External thermal louvres would automatically adjust to changes in weather and lighting and raking roof-mounted reflectors were designed to track the path of the low northern sun.

The high energy consumption of air-conditioning was to have been avoided by the installation of large volume heating and ventilation equipment on the underbelly of the building. The scheme was abandoned when the clients decided to retain their existing offices in Oslo.

o The telework for the routine processing and the work at a ”third place” for the creative activity

Interesting conclusions on the working style after the pandemic seemed to have appeared during this period. Thus, the non-creative, routine activity can be done at home, while the creative meetings can occur elsewhere. ”Elsewhere„ can well be the headquarters of the company or a non-conventional location – such as a community building, Starbucks café or a beautiful area, proper to outdoor activities. ”Elsewhere” becomes a new component of a work package.

This trend had already been anticipated by the project The Hub in the Swiss Alpine village of La Punt. A new kind of visitor – the working tourist, has been created over there, away from the city. The project finds a solution not only to assure the healthy working environment, but also to safeguard forgotten and abandoned villages. (Annex Photo 12)

The revival of villages in decline is a trend that positively impacts on local businesses and seems to be preferred by the young generation. The project in La Punt village has illustrated a trend against leaving villages by youngsters. The inspiration for this project was a workshop taking place in the Madrid Headquarters of the Norman Foster Foundation when two entrepreneurs from La Punt witnessed the debates among 10 graduates and a similar number of mentors on issues related to the effects of global warming, robotics and artificial intelligence. The prevailing theme was the youth and his engagement in environmental issues. The young people proved having more health consciousness than their forebears.

In the same line, urban farming seem to be the future solution for the supply of food to the cities and the potential of urban agricultural fields with hydroponics to save water and have dramatically increased yields, to reduce the transport distances and deliver fresher produce at less cost.

· The hospitals lay stress on the therapeutic effect of nature and domestic atmosphere

The hospital facilities were brought to the fore by the pandemic and the achievements of the company F+P also prove a forefront approach to this topic. Its projects underline and maximize the therapeutic role of natural environment on patients. The projects also highlight the importance of the environment beneficial to socialization for medical research, the architect considering that ”the great discoveries are rather the result of opinion exchanges at the coffee house than official debates”.

The University of Iowa Stead Family Children’s Hospital, as the first phase of modernization of the university’s healthcare campus and improvement of the quality of medical care, is dedicated to saving children’s lives and focuses on making the often traumatic experience of being in a hospital more humane for the young patients and their families.

The 140-bed hospital is conceived as a bright, uplifting environment. Colour is used to this effect, and so are the transparent façades opening views to the landscape beyond and the atrium ‘lightwells’ bringing light and nature into the interior. Playrooms for children and living rooms for families are situated throughout the building. The bedrooms are focused on the needs of the patient, being endowed with a large picture window to create a visual connection with the outside world. There are also family zones, where parents can stay with their children. Integrated brise-soleils provide protection from the sun, as well as light and shade on the interior.

Maximizing the therapeutic qualities of the natural setting, the patient tower extends into a new public park. The ground level is transparent and permeable and incorporate public spaces.

Maggie’s Centres provide a ‘home away from home’, a place of refuge where people affected by cancer can find emotional and practical support. Inspired by the blueprint for a new type of care set out by Maggie Keswick Jencks, they place great value upon the power of architecture to lift the spirits and help in the process of therapy. The Centre aims to establish a domestic atmosphere in a garden setting located a short walk from The Christie Hospital and its leading oncology unit and reflects the residential scale of the neighborhood. The roof rises in the centre to create a mezzanine level, naturally illuminated by triangular roof lights and it is supported by lightweight timber lattice beams acting as natural partitions between different internal areas, visually dissolving the architecture into the surrounding gardens. The centre combines a variety of spaces, from intimate private niches to large areas like a library, exercise rooms and places to gather. In the central area, where the kitchen is located, there is a focus on natural light, greenery and garden views. The plan is punctuated by landscaped courtyards and extends into a wide veranda, which is sheltered by a deep overhang of the roof. Sliding glass doors open the building up to a garden setting. Each treatment room faces its own private garden. The south end of the building extends into a greenhouse which provides a garden retreat, where people can gather, work and enjoy the outdoors activities. It is a space to grow flowers, vegetables and fruit that are used at the centre, giving the patients a sense of purpose at a time when they may feel at their most vulnerable.

The Pavilion for the University of Pennsylvania Health System (Penn Medicine) is a flexible hospital facility that will serve as a blueprint for the ‘hospital of the future’, providing the most cutting-edge medical care in the world.

The design is sustainable, efficient and sensitive to its surroundings, responding to the needs of patients, material and spiritual, measurable and intangible. By prioritizing light and views for the patients, visitors and staff, the design takes a holistic view on the health system. The unique, flexible planning system for the units breaks the building down into ‘neighborhoods’ which signify a smaller, more human scale, providing a feeling of a more sensitive and personalized environment. Each floor features a family ‘living room’ for people accompanying the patient; the size and configuration of the bed units are flexible to be more reactive to changing needs and patient demands.

Flexibility is also a key consideration, as the most unpleasant experiences for a patient are when they are constantly wheeled in and out of different rooms to accommodate the changing level of medical care they require.

The 500 private patient rooms, adaptable to any level of health care, have been designed to support varying types of patient care and are spacious enough for family to stay with the patient. They also feature an interactive wall that allows the patients to customize their own environment, while also working as a real-timeinformation and teaching aid for doctors. As medical science evolves, patient priorities will continue to change and new technologies will need to be incorporated – many of which we cannot yet predict. In this way, the building provides a platform for the future delivery of medical assistance.

It is a new health pavilion that looks to the future of integrated and interactive health education. The brief identified an area that could be developed into a campus, combining two Schools of Medicine, a School of Dental Medicine and a School of Nursing.

The Samson Pavilion marks a significant investment in the future of health education, which brings together the previously separate medical education programs into a single, multidisciplinary building.

Key elements of each school are arranged around a large internal courtyard, maintaining their own identities, but with a series of layered shared spaces. Spatial efficiency was greatly increased through space utilization studies and analysis of teaching methods and also through the creation of flexible spaces. The different faculties share teaching spaces, admin areas, lecture halls, recreational areas and technical teaching facilities, as well as improved building services, storage and amenities such as cafeterias etc.

The central courtyard is the social heart of the pavilion. Generously top-lit through linear skylights, the space is meant for informal work meetings.

The daylight and climate analysis by the structural and environmental teams working alongside the architects informed the design of the roof of the central courtyard. The heavy snowfalls in the region drove the structural design and the shading is provided by the truss cladding allowing more light around the perimeter circulation spaces.

The pavilion allows students from the three medical schools to learn together, inspire each other and collaborate using a combination of the latest digital technology and shared social spaces, reinforcing the building’s pioneering purpose to create better healthcare for all.

The Magdi Yacoub Global Heart Center in Cairo is a state-of-the-art hospital, forming part of an integrated health and medical research zone. One of its advantages is the striking views of the Pyramids of Giza and the lush, verdant landscape that seeks to optimise the overall patient experience.

The 300-bed hospital responds to the needs of patients, their families and the medical staff. The main access to the site is through a pedestrian plaza located at the end of a shaded welcoming route leading to a canopy that marks the entrance. The ground floor comprises comprehensive diagnosis and treatment facilities, including an intensive care unit, a large outpatient clinic and rehabilitative departments. Several courtyards bring natural light into the building, while also aiding orientation. Each ward provides special landscaped views. The patient rooms on the upper floors are sheltered by sculptural shell-like roof structures reminiscent of the feluccas on the Nile.

The design uses soft and warm colours throughout the interior, influenced by the psychology of colours and the Egyptian history.

A green terrace containing a canteen, children’s nursery and other socializing spaces – inspired by the local tradition – provides a spill-out space for the staff and visitors. The focus on natural light, greenery and views out creates an environment that supports health. Rich, native flora has been introduced to the site, creating a ring of green interwoven with pedestrian paths and quiet contemplative spaces.

Norman Foster has recently embarked on a research into scientifically evaluating buildings, jointly with the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health and Joseph Allen, the co-author of the book Healthy Buildings. ”Allen and I made the point that the extra costs in a new building were relatively marginal ”. In any case, the ”unhealthy” buildings, with a high energy consumption and carbon dioxide emissions can no longer survive and cannot cope with the competition and the current requirements.

· Cities will be greener by the conversion of large areas dedicated to roads and traffic to pedestrians, bikers, terraces, parks and pathways

Foster suggests that the city will become greener as the means of personal mobility are rapidly changing and young people prove to be less interested in using the car. The average street in London which provides two thirds of its width to vehicles is limiting the space for other uses. Foster's vision would see this space transformed. With parking consolidated in empty plots nearby, the street regains a community focus, with cyclists and pedestrians prioritized and the area reclaimed for planting, seating and more efficient waste management.

Many cities have already taken advantage of deserted roads in the pandemic to create new cycle lanes. Paris alone is creating 650km of them. The SkyCycle Foster project scheme for London provides cycle routes, as suspended lightweight platforms, 'whizzing' 12,000 commuters an hour through the city and providing aerial connectivity to various destinations.

A new generation of monorails is underway, which can provide aerial mobility and free up the ground plane for pedestrians. Research work by the Norman Foster Foundation has shown the potential to combine these systems with control of the local microclimate – cleaning the air of thoroughfares that were polluted both in the past and at present.

· Pedestrians reclaim streets and squares

The transformation of Trafalgar Square is the result of a careful balancing act between the needs of traffic and pedestrians, the ceremonial and the everyday, the old and the new.

The Square, laid out in the 1840s by Charles Barry and dominated by Nelson’s Column, is lined by significant buildings. Yet, despite its grandeur, by the mid-1990s, the square had become choked by traffic. After consultations involving 180 separate institutions and thousands of individuals, the project proposed the closure of the north side of the Square to traffic and the creation of a broad new terrace with a flight of steps and a café, providing an appropriate setting for the National Gallery.

Improvements in the Square and the adjacent streets were proposed, including new seating, lighting and traffic signage and a paving strategy with visual and textural contrasts.

Marseille’s Vieux Port, one of the grand Mediterranean ports, which had become inaccessible to pedestrians and had been cut off from the city life, has been regenerated for the community, creating a pedestrian area, transforming the quaysides as a civic space and setting up venues for performances and events. Its transformation was part of the preparations for Marseille’s status as European Capital of Culture 2013.

Enlarging the pedestrian space, removing the technical installations and replacing the quaysides with new platforms and clubhouses over the water, the landscape design, developed with Michel Desvigne, which eliminates kerbs and improves accessibility, as well as maximizing the functional flexibility allowed for the improvement of the background, the increase of liveliness and the reclamation of the port for the social life of the city using very discreet means. At Quai de la Fraternité, a blade of stainless steel shelters a flexible new pavilion, an open ‘ombrière’ where events and markets can take place.

(The batch of the projects presented was achieved by Ileana TUREANU, based on the documentation supplied by Foster+Partners Company)